Transylvanian Unitarianism Down to this Day

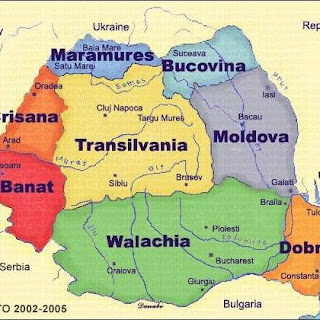

The Unitarian Church in Transylvania was first recognized by the 1568 Edict of Torda, which also established religious toleration among the four allowed religions: Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, and Unitarian. In its early years, the Unitarian Church attracted members in large numbers, and grew to 425 parishes.

Still the Catholics as well as both Protestant churches reviled the Unitarians as heretics. Transylvania’s King John died in 1571, just a couple years after officially converting to Unitarian himself. Having no heirs, he was succeeded by Istvan Bathory, a Catholic.

The press of Gyulafehérvár was taken away from the Unitarian control.

The Diet of 1572 did not dare to repeal the Edict of Toleration, so it prohibited anyone to change religion. The people of Transylvania had freedom of religion – but only once. A person could freely choose, once – and then was stuck with the choice.

Also in 1572, Ferenc David, whose mind was always probing and questioning, as Unitarian minds tend to do, went so far as to deny the necessity of invoking Jesus Christ in prayer. Prayer, he said, may be addressed simply to God. This was deemed to be a change in religion, and David was arrested and imprisoned. He died in prison 7 years later.

Without a sympathetic king, and without its leading advocate, Transylvanian Unitarians had a hard go of it for about a century, but the faith survived, even down to this day. Today, in Romania, there are 110 Unitarian priests and 141 places of worship. Church officials in Romania estimate 80,000 to 100,000 Romanians are Unitarian – an enduring legacy of the innovative thinking of Queen Isabella, her son, King John Sigismund, and the impassioned advocate of freedom, Ferenc David.

NEXT: The Reformation in Italy

Sermons, Prayers, and Reflections from First Unitarian Church, Des Moines, IA (2023-2025) and Community Unitarian Universalist Congregation, White Plains, NY (2013-2023)

2020-12-26

2020-12-23

UU Minute Christmas Special

Our Holiday

Unitarian History makes clear that Christmas is the Unitarian Holiday!

Prior to 1850, Christmas celebration was

Christmas today means putting a tree indoors, and decorating it. That was a practice in Germany, brought to the United States in the early 1800s by the Unitarian minister Reverend Charles Follen.

Christmas means Old Ebenezeer Scrooge’s heart opens up to compassion and joy. In 1843 a Unitarian named Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol. A Christmas Carol remains the most widely read-aloud book in the English-speaking world, and is theatrically performed in hundreds of venues around the country every year. Other popular Christmas tales such as "It's a Wonderful Life" and "How the Grinch Stole Christmas" are but re-workings of Charles Dickens' Unitarian gospel. Dickens’ tale of generosity, gratitude, and the joy of family gathering is fundamentally Unitarian.

Christmas means dashing through the snow, one-horse open sleighs, bells that jingle, and laughing, all the way. That’s the song “Jingle Bells,” by the Unitarian James Pierpont. "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” is by Unitarian Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. John Bowring, who gave us "Watchman Tell Us of the Night," and Noel Regney, who wrote “Do you hear what I hear?” were also Unitarians.

Christmas also means a focus on ending war and violence. “Peace on Earth, to all goodwill,” say the angels in the gospel of Luke. For most of the history of Christendom, Luke’s angels have been taken as referring to a private, personal peace. Few imagined that peace on earth actually meant we should stop killing each other.

Then, in 1849, with a war in Europe, and the US war with Mexico weighing on his mind, Unitarian Minister Rev. Edmund Hamilton Sears wrote a carol, “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” that made “peace on earth” about ending war.

His lyrics raised objections from a number of Christian conservatives of the time. They said, contemptuously, that Sears’ hymn was just the sort of thing you would expect of a Unitarian. They were right about that.

If Christmas season today is a time when our hopes turn to ending war and truly bringing peace on earth, it is because a Unitarian minister wrote a song inviting us to imagine the day,

Unitarian History makes clear that Christmas is the Unitarian Holiday!

Prior to 1850, Christmas celebration was

"culturally and legally suppressed and thus, virtually non-existent. The Puritan community found no Scriptural justification for celebrating Christmas, and associated such celebrations with paganism and idolatry." (Wikipedia)Then, a radical transformation of Christmas began, and Unitarians were at the forefront in most of the transforming.

Christmas today means putting a tree indoors, and decorating it. That was a practice in Germany, brought to the United States in the early 1800s by the Unitarian minister Reverend Charles Follen.

Christmas means Old Ebenezeer Scrooge’s heart opens up to compassion and joy. In 1843 a Unitarian named Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol. A Christmas Carol remains the most widely read-aloud book in the English-speaking world, and is theatrically performed in hundreds of venues around the country every year. Other popular Christmas tales such as "It's a Wonderful Life" and "How the Grinch Stole Christmas" are but re-workings of Charles Dickens' Unitarian gospel. Dickens’ tale of generosity, gratitude, and the joy of family gathering is fundamentally Unitarian.

Christmas means dashing through the snow, one-horse open sleighs, bells that jingle, and laughing, all the way. That’s the song “Jingle Bells,” by the Unitarian James Pierpont. "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” is by Unitarian Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. John Bowring, who gave us "Watchman Tell Us of the Night," and Noel Regney, who wrote “Do you hear what I hear?” were also Unitarians.

Christmas also means a focus on ending war and violence. “Peace on Earth, to all goodwill,” say the angels in the gospel of Luke. For most of the history of Christendom, Luke’s angels have been taken as referring to a private, personal peace. Few imagined that peace on earth actually meant we should stop killing each other.

Then, in 1849, with a war in Europe, and the US war with Mexico weighing on his mind, Unitarian Minister Rev. Edmund Hamilton Sears wrote a carol, “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” that made “peace on earth” about ending war.

"Beneath the angel strain have rolledhe decried.

two thousand years of wrong,

And man at war with man hears not

the love song which they bring,"

His lyrics raised objections from a number of Christian conservatives of the time. They said, contemptuously, that Sears’ hymn was just the sort of thing you would expect of a Unitarian. They were right about that.

If Christmas season today is a time when our hopes turn to ending war and truly bringing peace on earth, it is because a Unitarian minister wrote a song inviting us to imagine the day,

"when peace shall over all the earthThis really is our holiday. From the Christmas tree, to the jingling bells, to the Scrooge story, to the message of peace on earth, Unitarians made Christmas what it is today.

its ancient splendors fling,

and the whole world give back the song

which now the angels sing."

2020-12-19

UU Minute #21

The Connection: Reason

Unitarians have been around 450 years, and our history is rooted in two ideas:

Actually, there is a logical connection: reason. It was the exercise of reason that produced the rational critique of trinitarianism. And the proper function of reason depends on the freedom allowed by tolerance. Any ideology that isn’t rationally defensible can only rely on authoritarian coercion to secure adherents.

Ferenc David, the Transylvanian theologian and King John Sigismund’s court preacher, was an impassioned advocate for both the unity of God and freedom of conscience. His words are part of Unitarian Universalism to this day, and appear in the back of our hymnal, reading number 566, which includes the words in David’s native Hungarian:

NEXT: Transylvanian Unitarianism Down to this Day

Unitarians have been around 450 years, and our history is rooted in two ideas:

- rational critique of the trinity, and

- tolerance of diversity of opinion.

Actually, there is a logical connection: reason. It was the exercise of reason that produced the rational critique of trinitarianism. And the proper function of reason depends on the freedom allowed by tolerance. Any ideology that isn’t rationally defensible can only rely on authoritarian coercion to secure adherents.

Ferenc David, the Transylvanian theologian and King John Sigismund’s court preacher, was an impassioned advocate for both the unity of God and freedom of conscience. His words are part of Unitarian Universalism to this day, and appear in the back of our hymnal, reading number 566, which includes the words in David’s native Hungarian:

Egy Az Isten– meaning, God is one. As selected, adapted, and arranged by UU minister Reverend Richard Fewkes, here is that reading from Ferenc David:

In this world there have always been many opinions about faith and salvation.

You need not think alike to love alike.

There must be knowledge in faith also.

Sanctified reason is the lantern of faith.

Religious reform can never be all at once, but gradually step by step.

If they offer something better, I will gladly learn.

The most important spiritual function is conscience, the source of all spiritual joy and happiness.

Conscience will not be quieted by anything less than truth and justice.

We must accept God’s truth in this lifetime. Salvation must be accomplished here on earth.

God is indivisible.

Egy Az Isten.

God is one.

NEXT: Transylvanian Unitarianism Down to this Day

2020-12-14

Principles and Promises, part 2

The principles of the Unitarian Universalist association express our covenant, it’s true. The words of Community UU Congregations's mission are also covenantal:

“We covenant to nurture each other in our spiritual journeys, foster compassion and understanding within and beyond our community, and engage in service to transform ourselves and our world.”That’s also an expression of covenant. But CUUC was a congregation held by covenant long before 2014 when we adopted our current mission statement, and Unitarian Universalists have been a people of covenant from long before 1985 when we adopted our current set of principles.

Before that, the covenant was expressed along similar lines in 1961 in the initial documents when the Unitarian Universalist Association was created from the consolidation of the Unitarians and the Universalists. And before that both Unitarian and Universalists had expressed the covenant in various ways. In the late 19th-century, for instance, James Blake expressed it in words that are still in our hymnal today:

“Love is the spirit of this church, and service its law. This is our great covenant: to dwell together in peace, to seek the truth in love, and to help one another.”The expression of the covenant is not the covenant. The word "moon" is not the moon. The expression of the covenant is some set of words. The covenant itself is the mysterious force that holds us together and is ultimately beyond words. The covenant of love, of fidelity to one another, the sacred promise to walk together – the whole truth -- is eternal. The ways that we give expression to that eternal must fit the particular culture and time.

Unitarians, Universalists, and Unitarian Universalists have long understood that every generation should give its own expression to the covenant that binds us. In 1961, when Unitarians and Universalists came together to form the Unitarian Universalist Association, our initial documents included a set of principles. One generation later -- right on schedule -- we engaged a process to re-write them. That process culminated in the 1985 covenant of principles.

Another generation went by, and that brought us to the late aughts. For two years, our congregations were enjoined to discuss possible revisions to our Article II by-laws, which includes the principles, and submit ideas to the Commission on Appraisal. I remember leading classes and meetings about that at the congregations I was serving at the time. The Commission received the input and produced a proposed revision, which came before the General Assembly in 2009 in Salt Lake City for initial approval. Initial approval would have sent the proposal to the congregations for a year of discussion, with final approval subject to vote of the 2010 General Assembly.

The proposed changes in the principles themselves were slight. There would still be seven of them. The third principle was shortened from

“acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations”to simply

“acceptance of one another and encouragement of spiritual growth.”The fifth principle was similarly shortened from

“the right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large”to simply

“the right of conscience and the use of democratic processes.”The seventh principle changed

“respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part”to

“reverence for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.”The other four principles were not changed at all. A more substantive change was proposed for the preamble to the seven principles. It would have changed from:

"We, the member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association, covenant to affirm and promote:"to

"Grateful for the gift of life, we commit ourselves as member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association to embody together the transforming power of love as we covenant to honor and uphold:"The proposed changes to the sources section was much greater – it would have replaced our six sources with three descriptive, rather prosaic, paragraphs.

Moreover, the proposal added a paragraph after the principles, and then added a section on inclusion that said:

“Systems of power, privilege, and oppression have traditionally created barriers for persons and groups with particular identities, ages, abilities, and histories. We pledge to do all we can to replace such barriers with ever-widening circles of solidarity and mutual respect. We strive to be an association of congregations that truly welcome all persons and commit to structuring congregational and associational life in ways that empower and enhance everyone’s participation.”This would have replaced the existing section on anti-discrimination with this fuller expression of commitments to antiracism and multiculturalism (Report of The Commission on Appraisal On The Mandated Review of Article II of the UUA Bylaws).

I was there in Salt Lake City, 2009, when moderator Gini Courter called for the vote on the Article II bylaws change -- and the yellow voting cards were held aloft by those in favor, and then by those opposed to the proposed revision. It looked like the same number on each side. So she called again for the Pro to raise their voting cards, and this time the GA counters systematically went down the rows tallying the votes, and then the same was done for the Con. When the final tally was in, 573 delegates had voted to send the proposal to the congregations – and 586 voted not to.

I voted for the revisions, but the stronger feelings in the room tended to be on the Con said – and most of it was related to the change in the sources. The new section on inclusion was generally supported, but our rules didn’t allow us to vote on the parts separately. The Commission on Appraisal's proposal had to be voted up or down as a whole. And it was voted down.

Today the process of considering changes is again before the denomination. The covenant is eternal. The words we choose to express the covenant must address the needs of the time. More than a decade after our last concerted effort to freshen our expression for a new generation yielded no results, our Association has again initiated the process for review. One proposal is to add an 8th principle.

Affirm and promote journeying toward spiritual wholeness.How shall we journey toward wholeness?

By working to build a Beloved Community.What kind of Beloved community?

A diverse, multicultural Beloved Community.How shall we do that?

By our actions.Actions that what?

That dismantle racism and other oppressions.Can’t do that without accountability.

Right. Actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions.And where is this racism and other oppressions we’re going to accountably dismantle?

It’s in ourselves and our institutions.So let us say – say out loud and say officially – that the call of covenant, the call to live bound, and bound together, by promise, includes that we promise to

affirm and promote:May it be so.

journeying toward spiritual wholeness

by working to build a diverse multicultural Beloved Community

by our actions

that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions

in ourselves and our institutions.

Amen.

Principles and Promises, part 1

See also: Principles and Promises, part 2

We are Unitarian Universalists. We are a people of passion and intelligence – of moral imagination, creativity, and engagement.

We are a people NOT of creed; we are creedless. In this regard, we are not unique. We have this in common with, oddly enough, the Southern Baptist Convention, which is officially creedless, as is the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).

We go a little further in declaring not only that we have no creed, but that, for us, religion itself is not about what one believes. Beliefs are an incidental, peripheral, and ultimately unnecessary aspect of religion, of spirituality. For us, religion is about three things:

- Religion is about how you live: the ethics and values that guide your life.

- Religion is about community – the people you come together with, and share rituals to affirm your community connection.

- And religion is about experience – the experience of awe and wonder, of mystery, transcendence, oneness – the experience of simultaneous intimacy and ultimacy.

We are a people not of creed. We are also a people not of canon. We have no canonical bible. Of all the words and writings offering insights, telling the story of who we are as people, of how reality is – powerful words of wisdom and inspiration – we do not select a few of them to designate as our holy scripture while all else is, at best, supplement or commentary, or else entirely secular.

For Jews, the canon is the 39 books of the Tanakh, and especially the 5 books of the Torah. For Catholics, those 39, plus 7 more, plus the 27 books called the New Testament, making 73, are canonical. The Orthodox Bible adds 6 more books, for a canon of 79 books. When the Protestants came along, they pared back to just 66 books: the 39 books of the Hebrew Bible, plus the 27 New Testament books.

We are canonless as well as creedless. We look to all the world’s traditions for wisdom and insight, and are ever open to new work that we may find limns the ineffable, reaches for what cannot be grasped, or points us a way. Our canonlessness more radically separates us from other Western faith traditions than our vaunted creedlessness does.

We are a people neither of creed nor of canon, but of covenant. We are bound, and bound together, not by common belief, nor by common scripture of study, but by a common promise. Covenant – in the religious sense – is not like a contract, where if one party doesn’t live up to their part the other side doesn’t have to live up to theirs. Covenant continues to bind us even when we break covenant.

To live the way of covenant is to be constantly breaking it, to be constantly failing, and to be constantly called back, or called forward, to the promise of our promise. The Sufi mystic Rumi expressed this in a poem well-known to us in its Coleman Barks translation.

Come, come, whoever you are,These are the words of one of our hymns in our hymnal, but it is not the full poem. The rest of Rumi’s poem adds:

Wanderer, worshiper, lover of leaving.

It doesn’t matter.

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Come.

Come, even if you have broken your vows a thousand times.The covenant continues to call and to compel, to beckon us toward the promise of a life constituted by promising, no matter how many times we may have broken or will break our vow.

Come, yet again, come.

Also unlike a contract, which might lead the parties into court where a judge will render a ruling on what the contract’s terms mean and whether the party’s actions satisfy the terms, you alone are final arbiter of what the covenant requires of you now. We are each properly informed by our community and its collective discernments -- our understanding of the covenant's meaning is a product of our community engagement -- and then it's up to you to discern what the covenant means to you.

And what is our covenant, the promise that binds us, that fashions us into a people? I could tell you it is here in our principles set forth in the bylaws of the Association:

We, the member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association, covenant to affirm and promote:I could tell you that is our covenant, and that would be true. Those are words that call to us as Unitarian Universalists, that we experience, in proportion to the role that our faith has in our lives, as compelling and beckoning. Those are the promises that we keep as we can and sometimes break, that we orient our lives by – the vows that point our way, howsoever we stray.

- The inherent worth and dignity of every person [or: every being]

- Justice, equity and compassion in human relations

- Acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations

- A free and responsible search for truth and meaning

- The right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large

- The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all

- Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

It’s true this is our covenant, but it’s not the whole truth of the people we are. Not the whole truth.

See also: Principles and Promises, part 2

2020-12-12

UU Minute #20

The Edict of Torda

Queen Isabella had made the first move toward religious toleration about a decade before. In 1557, she decreed that Catholic and Lutheran would each be recognized and allowed. A bit later, Calvinism had been recognized.

King John Sigismund’s court preacher, Ferenc David, and his counselor and physician, Giorgio Biandrata, together launched a series of publications and took part in public debates about religion, each lasting from several days to over a week. David and Biandrata interwove arguments for a Unitarian theology and arguments for religious tolerance – and persuaded the King himself. It was David who was the powerful and passionate voice in Torda in 1568 calling on the delegates to adopt the edict that he brought before them.

In the centuries after Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation, all of Europe was embroiled in religious conflict – often violent. When every other leader in Europe was choosing a side and seeking by force to impose it throughout their realm – under the assumption that a populace that shared a government must also share a religion -- Transylvania alone had the wildly radical notion of religious freedom -- of using the powers of the state not to promote the state’s preferred religion, but to protect multiple religions.

NEXT: The Connection: Reason

“...in every place the preachers shall preach and explain the Gospel each according to his understanding of it, and if the congregation like it, well. If not, no one shall compel them for their souls would not be satisfied, but they shall be permitted to keep a preacher whose teaching they approve. Therefore none of the superintendents or others shall abuse the preachers, no one shall be reviled for his religion by anyone, according to the previous statutes, and it is not permitted that anyone should threaten anyone else by imprisonment or by removal from his post for his teaching. For faith is the gift of God and this comes from hearing, which hearing is by the word of God.” (Edict of Torda, 1568)The Edict of Torda, named for the Transylvanian town where it was adopted in 1568, gave state sanction to four religions: Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, and Unitarian. A congregation that was one of those variants of Christianity could not be persecuted, and could freely elect its preacher.

Queen Isabella had made the first move toward religious toleration about a decade before. In 1557, she decreed that Catholic and Lutheran would each be recognized and allowed. A bit later, Calvinism had been recognized.

King John Sigismund’s court preacher, Ferenc David, and his counselor and physician, Giorgio Biandrata, together launched a series of publications and took part in public debates about religion, each lasting from several days to over a week. David and Biandrata interwove arguments for a Unitarian theology and arguments for religious tolerance – and persuaded the King himself. It was David who was the powerful and passionate voice in Torda in 1568 calling on the delegates to adopt the edict that he brought before them.

In the centuries after Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation, all of Europe was embroiled in religious conflict – often violent. When every other leader in Europe was choosing a side and seeking by force to impose it throughout their realm – under the assumption that a populace that shared a government must also share a religion -- Transylvania alone had the wildly radical notion of religious freedom -- of using the powers of the state not to promote the state’s preferred religion, but to protect multiple religions.

NEXT: The Connection: Reason

2020-12-05

UU Minute #19

King John Comes Around

King John Sigismund’s rule of Transylvania began in 1559 when his mother, Isabella, died. He was 19.

John, like his mother, was unusually interested in religion – both as a tool of statecraft and from a genuine interest in discerning the truth for its own sake. Born and raised Catholic, John converted to Lutheranism at age 22. At age 24, John switched to Calvinism and appointed Ferenc David as Court Preacher.

David and Giorgio Biandrata, John’s physician and trusted counsellor, now at court together, began collaborating in the development of the two ideas that would be central to Unitarianism:

While the appointed auditors ruled the debate inconclusive, the king liked what he heard from Biandrata and David, and provided them a press with which to publish Unitarian ideas to a wider audience. The next year, 1567, Biandrata and David co-authored False and True Knowledge of God, echoing Miguel Serveto’s points. Repeatedly they insisted that Christ and the Apostles held a simple and straightforward doctrine, which was corrupted by philosophical sophistry epitomized by Trinitarianism.

By the end of 1567, King John was persuaded. He, along with Biandrata and David, were now Anti-trinitarians, though there wasn’t yet a Unitarian denomination. That would come in 1568, with the Edict of Torda.

NEXT: The Edict of Torda

King John Sigismund’s rule of Transylvania began in 1559 when his mother, Isabella, died. He was 19.

John, like his mother, was unusually interested in religion – both as a tool of statecraft and from a genuine interest in discerning the truth for its own sake. Born and raised Catholic, John converted to Lutheranism at age 22. At age 24, John switched to Calvinism and appointed Ferenc David as Court Preacher.

David and Giorgio Biandrata, John’s physician and trusted counsellor, now at court together, began collaborating in the development of the two ideas that would be central to Unitarianism:

- criticizing trinitarianism, including rejecting the deity of Jesus Christ – and

- upholding religious toleration.

While the appointed auditors ruled the debate inconclusive, the king liked what he heard from Biandrata and David, and provided them a press with which to publish Unitarian ideas to a wider audience. The next year, 1567, Biandrata and David co-authored False and True Knowledge of God, echoing Miguel Serveto’s points. Repeatedly they insisted that Christ and the Apostles held a simple and straightforward doctrine, which was corrupted by philosophical sophistry epitomized by Trinitarianism.

By the end of 1567, King John was persuaded. He, along with Biandrata and David, were now Anti-trinitarians, though there wasn’t yet a Unitarian denomination. That would come in 1568, with the Edict of Torda.

NEXT: The Edict of Torda

2020-11-28

UU Minute #18

Ferenc David and the Unitarian Mind

Ferenc David was born in Transylvania, in 1520. He was raised Catholic – went away to the University of Wittenberg to study Catholic theology. Wittenberg, you’ll remember, is where the Protestant Reformation began in 1517 when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the church door there. David returned home in 1551, at age 31, having been exposed to Lutheran ideas, but still a Catholic: rector of a Catholic school, then a Catholic parish priest.

Lutheranism grew in Transylvania, and, along with it, hostility toward Catholics. A number of Catholic clergy switched over, and Ferenc David joined them. He became a Lutheran minister and then Lutheran bishop. David gained a great reputation as a brilliant debater upholding Lutheranism against the Calvinists.

And then something happened that’s rather revealing about what we might call the Unitarian Mind. Psychologists will tell you that for most people, the exercise of arguing for a position increases their unbending commitment to that position. But for Ferenc David, fiercely debating against the Calvinists actually increased his sympathy for their position. At age 39, Ferenc David switched over to Calvinism.

David and Giorgio Biandrata met in 1564, and later that year, David was appointed King John Sigismund’s court preacher, and also bishop of the Calvinist church in Transylvania. David and Biandrata were thus able to have many conversations about further reform of doctrines, including abandoning Trinitarianism. David and Biandrata became the founding figures of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania.

David’s capacity to listen to those he disagreed with, to empathize with his opponents, and to be open to being persuaded by them – to continue to grow and change throughout life -- has been a key aspect of the Unitarian Mind from its beginnings.

NEXT: King John Comes Around

Ferenc David was born in Transylvania, in 1520. He was raised Catholic – went away to the University of Wittenberg to study Catholic theology. Wittenberg, you’ll remember, is where the Protestant Reformation began in 1517 when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the church door there. David returned home in 1551, at age 31, having been exposed to Lutheran ideas, but still a Catholic: rector of a Catholic school, then a Catholic parish priest.

Lutheranism grew in Transylvania, and, along with it, hostility toward Catholics. A number of Catholic clergy switched over, and Ferenc David joined them. He became a Lutheran minister and then Lutheran bishop. David gained a great reputation as a brilliant debater upholding Lutheranism against the Calvinists.

And then something happened that’s rather revealing about what we might call the Unitarian Mind. Psychologists will tell you that for most people, the exercise of arguing for a position increases their unbending commitment to that position. But for Ferenc David, fiercely debating against the Calvinists actually increased his sympathy for their position. At age 39, Ferenc David switched over to Calvinism.

David and Giorgio Biandrata met in 1564, and later that year, David was appointed King John Sigismund’s court preacher, and also bishop of the Calvinist church in Transylvania. David and Biandrata were thus able to have many conversations about further reform of doctrines, including abandoning Trinitarianism. David and Biandrata became the founding figures of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania.

David’s capacity to listen to those he disagreed with, to empathize with his opponents, and to be open to being persuaded by them – to continue to grow and change throughout life -- has been a key aspect of the Unitarian Mind from its beginnings.

NEXT: King John Comes Around

2020-11-21

UU Minute #17

Biandrata and David Meet

People meeting each other for the first time is a common event. Some first meetings turn out to be historically notable.

The day Eleanor Gordon and Mary Safford first met – it was around 1860, and the two were children. They would both grow up to become Unitarian ministers and the nucleus of the Iowa Sisterhood movement in Unitarian history.

The day Curtis Reese and John Dietrich first met – it was 1917 at the Western Unitarian Conference. The two would work together spearheading the Unitarian Humanist movement.

Another pivotal first meeting was that of Giorgio Biandrata and Ferenc David in 1564. If you had to pinpoint the day Transylvanian Unitarianism began, your best answer would be: that day.

We’ve mentioned the conflict between Lutherans and Calvinists over whether the body and blood of Christ were present in the bread and wine of the Lord’s supper – or whether these were simply symbols. And that the Transylvanian Diet of 1563 renewed and confirmed Isabella’s earlier edict of religious toleration, and that this didn’t much ease the conflict. The next year, 1564, a General Synod was called in Nagyenyed (now called Aiud), and the king sent “his most excellent Giorgio Biandrata” from the capital, Gyulafehervar (now called Alba Iulia) 30 km up the road to the synod to try to settle the controversy.

After days of debate, with Biandrata arguing for the Calvinist side, it was evident neither side would bend. The Calvinists then sought separate official recognition, which King John granted.

At that 1564 synod, Biandrata met Ferenc David, at that time also arguing for the Calvinist side. The two men were impressed with each other, and in private conversations each disclosed an interest in departing from Lutheranism rather farther than Calvinism did. That meeting was the beginning of what would become Unitarianism in Transylvania.

NEXT: Ferenc David and the Unitarian Mind

People meeting each other for the first time is a common event. Some first meetings turn out to be historically notable.

The day Eleanor Gordon and Mary Safford first met – it was around 1860, and the two were children. They would both grow up to become Unitarian ministers and the nucleus of the Iowa Sisterhood movement in Unitarian history.

The day Curtis Reese and John Dietrich first met – it was 1917 at the Western Unitarian Conference. The two would work together spearheading the Unitarian Humanist movement.

Another pivotal first meeting was that of Giorgio Biandrata and Ferenc David in 1564. If you had to pinpoint the day Transylvanian Unitarianism began, your best answer would be: that day.

We’ve mentioned the conflict between Lutherans and Calvinists over whether the body and blood of Christ were present in the bread and wine of the Lord’s supper – or whether these were simply symbols. And that the Transylvanian Diet of 1563 renewed and confirmed Isabella’s earlier edict of religious toleration, and that this didn’t much ease the conflict. The next year, 1564, a General Synod was called in Nagyenyed (now called Aiud), and the king sent “his most excellent Giorgio Biandrata” from the capital, Gyulafehervar (now called Alba Iulia) 30 km up the road to the synod to try to settle the controversy.

After days of debate, with Biandrata arguing for the Calvinist side, it was evident neither side would bend. The Calvinists then sought separate official recognition, which King John granted.

At that 1564 synod, Biandrata met Ferenc David, at that time also arguing for the Calvinist side. The two men were impressed with each other, and in private conversations each disclosed an interest in departing from Lutheranism rather farther than Calvinism did. That meeting was the beginning of what would become Unitarianism in Transylvania.

NEXT: Ferenc David and the Unitarian Mind

2020-11-19

Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

As Joseph lies in the pit, in his rejection and suffering, the way of forgiveness comes over him. It begins not by forgiving those who wronged him. This does not occur to him. It begins with a prayer that he be forgiven.

Joseph finds it a helpful device to personify this reality as God. “Not what I want,” he prays:

Thus, when he is pulled out and sold to Ishmaelites, he doesn’t speak up.

Thus Joseph comes to serve Potiphar for some years. He rises to a position of being in charge of Potiphar’s affairs. He is falsely accused, and thrown in prison. Yet here again he does not speak up in his own defense.

He counsels some people in prison, and does so so shrewdly that at last Pharaoh seeks his counsel – his ability to see the sense in what doesn’t seem to make sense. And this, too, is a feature of the Way of Forgiveness. It is the way of hope – not hope in the sense of a thing wished for – but hope as the understanding that things make sense, however they turn out.

Joseph is made the Pharaoh’s viceroy, and his job is to plan for the future. Even as he spends his days in the complex calculations and strategies of food storage for a time of famine, he does so without a sense of rejection or resistance to what will come, but simply a sense of compassion for people that they be provided for, and not come to starve. Even as he plans for a future, he is living in wonder of each present moment.

The famine comes, and his brothers show up begging for food. After testing them with some devices, eventually he reveals himself to them. First, he has to prove he really is their brother Joseph. So he recounts to them their crime of throwing him in the pit, then selling him into slavery. It’s not what he wants to dwell on, but it’s something he would only know if he really were their brother Joseph.

This is the language available for that time and culture for pointing to the illusion of control. The brothers never decided to hate the young Joseph’s arrogance – they simply found that they did. There was never a point of conscious decision to resent the particular selectivity of their father’s love – but resentment had arisen and consumed them nonetheless. Ultimately, it wasn’t they who had thrown Joseph into the pit, or sold him to Ishmaelites, but all the forces that made them into the sorts of human beings they were.

The Way of Forgiveness is the way that never needs to perform specific acts of forgiving, for it is based in the awareness that everything is always already forgiven.

May it be so. Amen.

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

As Joseph lies in the pit, in his rejection and suffering, the way of forgiveness comes over him. It begins not by forgiving those who wronged him. This does not occur to him. It begins with a prayer that he be forgiven.

“Forgive me, he prayed [silently], not to God but to his brothers, though he knew this was absurd. There was no way out. There were no solutions. There was nothing to do, nothing to pray but May your will be done. . . .” (Stephen Mitchell, Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness)It’s a prayer to let go of the ego’s thoughts about what should be, to open fully and unreservedly to reality just as it is.

Joseph finds it a helpful device to personify this reality as God. “Not what I want,” he prays:

“but what You want. I am not doing any of this, nor are my brothers. Whatever we think we are doing, we are all doing what is best in Your sight. We are all doing Your will, dear Lord, because we are all the work of Your hands.” (Mitchell)Whether reality is personified in this way or not, the way of forgiveness is the ongoing recognition and re-recognition that control is an illusion. Yes, we have responsibilities, and we must tend to them, but this is the narrower context of our lives. In the wider context, there is no control. This is the transformational awareness that, it seems, must have come over Joseph in the pit.

Thus, when he is pulled out and sold to Ishmaelites, he doesn’t speak up.

“He could have cried out against his brothers and, with his considerable eloquence, tried to move the Ishamelites’ hearts to take him home, where his wealthy father would pay them a large ransom. But he didn’t utter a word.” (Mitchell)The lesson here for us isn’t that we shouldn’t speak up in our own defense, protest injustices. Rather, it’s an invitation to feel our way into a more intuitive and receptive way of being. Joseph somehow intuited that what was happening was more – let us say, interesting – than being released back to his father. He could not have said why he felt that way.

Thus Joseph comes to serve Potiphar for some years. He rises to a position of being in charge of Potiphar’s affairs. He is falsely accused, and thrown in prison. Yet here again he does not speak up in his own defense.

He counsels some people in prison, and does so so shrewdly that at last Pharaoh seeks his counsel – his ability to see the sense in what doesn’t seem to make sense. And this, too, is a feature of the Way of Forgiveness. It is the way of hope – not hope in the sense of a thing wished for – but hope as the understanding that things make sense, however they turn out.

Joseph is made the Pharaoh’s viceroy, and his job is to plan for the future. Even as he spends his days in the complex calculations and strategies of food storage for a time of famine, he does so without a sense of rejection or resistance to what will come, but simply a sense of compassion for people that they be provided for, and not come to starve. Even as he plans for a future, he is living in wonder of each present moment.

The famine comes, and his brothers show up begging for food. After testing them with some devices, eventually he reveals himself to them. First, he has to prove he really is their brother Joseph. So he recounts to them their crime of throwing him in the pit, then selling him into slavery. It’s not what he wants to dwell on, but it’s something he would only know if he really were their brother Joseph.

“The next thing was to let these terrified men know that he had forgiven them, that he felt no anger or resentment, no residue from the event, and that he was standing before them with an open heart. Actually, forgiveness was an inaccurate word for what he was experiencing, since it implies that a magnanimous ‘I’ grants something to a not-necessarily-deserving ‘you.’ It wasn’t like that at all. He wasn’t granting anything or even doing anything. He realized that his brothers were guilty, but he also saw the innocence in that guilt.” (Mitchell)The Way of Forgiveness is distinct from a discrete act of forgiving, for it is grounded in:

“the realization that there is nothing to forgive. His brothers simply hadn’t known what they were doing. And given the violence of their emotions, there was nothing else they could have done.”He tells them, “don’t be troubled. Don’t blame yourselves.” He knows this reassurance won’t do much.

“His brothers would have to blame themselves; they wouldn’t be able to see their own innocence until their minds slowed down enough to understand their crime in the greater scheme of things. In the meantime, they would necessarily be grieved and angry at themselves, and they would suffer needlessly from a remembered – that is, from an imagined – past that they could neither retract nor change.”So he speaks to them in terms they might understand. He says, “God sent me ahead of you to save lives.”

This is the language available for that time and culture for pointing to the illusion of control. The brothers never decided to hate the young Joseph’s arrogance – they simply found that they did. There was never a point of conscious decision to resent the particular selectivity of their father’s love – but resentment had arisen and consumed them nonetheless. Ultimately, it wasn’t they who had thrown Joseph into the pit, or sold him to Ishmaelites, but all the forces that made them into the sorts of human beings they were.

The Way of Forgiveness is the way that never needs to perform specific acts of forgiving, for it is based in the awareness that everything is always already forgiven.

“Everything, even the most painful experience, turns out to be pure grace.”The Way of Forgiveness is thus also the Way of Hope – the only Way of Hope: the way of being present to the ineluctable wonder, beauty, mystery, and glory we cannot make and cannot mar.

May it be so. Amen.

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

Some people say, everything happens for a reason. It feels to them like there’s a divine plan. They say, there are no coincidences. They like such sayings as: "Everything works out in the end. If it hasn’t worked out, it’s not the end."

I don’t talk that way much. It seems to me to make just as much sense to say: "Nothing works out in the end. If it seems to have worked out, it’s not the end." Which sounds like one of those corollaries of Murphy’s Law, but what I mean is: it’s never the end. Whether things seem all neat and tidy or a total mess, it's never the end.

And there are coincidences. I don’t think events are part of a divine plan, and, while everything happens for causes, only some things happen for reasons – let alone a reason. But those who are drawn to speak that way are, I think, in their own way, pointing to something underlying, something important.

In this world of grief, loss, and pain, there is a glory somehow shining through. In the midst of all the oppression and injustice, there is a fundamental rightness about life and this world. Yes, wrong really is wrong. It’s also always in a wider context – a context within which everything is all right.

Take, for example, predation. The Fox hunts the rabbit – kills it and eats it. There is an inherent tragedy here: painful death for the rabbit, or else painful starvation death for the fox. Every day I vow to save all beings. How do I save both the Fox and the Rabbit? To save one is to doom the other, isn’t it? At least one well-known ethicist – Martha Nussbaum – argues that we should provide textured vegetable protein – fake meat – to all the predators, and perform enough vasectomies on prey animals that they don’t overpopulate. Then prey and predator alike could peacably live out their days. The lion could lie down with the lamb, without either of them fearing. I have yet to meet anybody who agrees with Martha Nussbaum about this.

Some years ago, trying to come to terms with this issue, I wrote this poem. It’s titled: Prayer to the Rabbit God.

And it brings forth our big and ultrasocial brains – that allow us not only amazing cleverness, but the capacity to share it, preserve it, and build on each other’s discoveries and strategies. All of this took massive heartless cruelty to bring forth.

Joseph’s way is to think in terms of a divine plan – but I offer to you that that is but a rhetorical flourish for orienting toward the beauty of life inseparable from its harsh pain.

Stephen Mitchell writes of the transformation that came over Joseph as he lay in that pit where his brothers had tossed him.

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

Some people say, everything happens for a reason. It feels to them like there’s a divine plan. They say, there are no coincidences. They like such sayings as: "Everything works out in the end. If it hasn’t worked out, it’s not the end."

I don’t talk that way much. It seems to me to make just as much sense to say: "Nothing works out in the end. If it seems to have worked out, it’s not the end." Which sounds like one of those corollaries of Murphy’s Law, but what I mean is: it’s never the end. Whether things seem all neat and tidy or a total mess, it's never the end.

And there are coincidences. I don’t think events are part of a divine plan, and, while everything happens for causes, only some things happen for reasons – let alone a reason. But those who are drawn to speak that way are, I think, in their own way, pointing to something underlying, something important.

In this world of grief, loss, and pain, there is a glory somehow shining through. In the midst of all the oppression and injustice, there is a fundamental rightness about life and this world. Yes, wrong really is wrong. It’s also always in a wider context – a context within which everything is all right.

Take, for example, predation. The Fox hunts the rabbit – kills it and eats it. There is an inherent tragedy here: painful death for the rabbit, or else painful starvation death for the fox. Every day I vow to save all beings. How do I save both the Fox and the Rabbit? To save one is to doom the other, isn’t it? At least one well-known ethicist – Martha Nussbaum – argues that we should provide textured vegetable protein – fake meat – to all the predators, and perform enough vasectomies on prey animals that they don’t overpopulate. Then prey and predator alike could peacably live out their days. The lion could lie down with the lamb, without either of them fearing. I have yet to meet anybody who agrees with Martha Nussbaum about this.

Some years ago, trying to come to terms with this issue, I wrote this poem. It’s titled: Prayer to the Rabbit God.

the rabbit god made bunniesSo that’s me expressing the glory shining through the tragedy, pain, and death – and without complacently exempting myself from that tragedy. There is, we might say, a kind of intelligence in the cruelty with which natural selection shapes species and ecosystems. I say “intelligence” without meaning to suggest intention. Natural selection has no intention, has no aim, no aforethought of where it’s going, yet through the passing of eons, the arms race of predator and prey – that cooperative competition of pushing each other to ever more sophisticated abilities – it brings forth ever more wondrous and unpredictable beauty: the sharp eye of the hawk, the graceful speed of the gazelle, the rabbit’s ear, the fox’s nose, the turtle’s shell, the porcupine’s quills, the skunk’s spray. It brings forth human bipedalism that makes us not as fast as our quadruped prey, but able to run longer distances, and our loss of body hair so we can dissipate heat while our prey succumbs to heat exhaustion over a long chase. Who could’ve seen that coming?

as morning brightened into day.

she gave them a green planet to eat,

made them love to hump

like rabbits

and love their babies.

bunnies make bunnies faster than plants grow, she noticed.

so, as evening darkened into night,

the rabbit god made foxes.

predation, she said,

will give my lovelies

sharp ears,

beautiful speed,

a touch of cleverness.

let them be grateful for the red fur death

and the fear that makes them so alert.

thus the rabbit god became the fox god too.

bodies are made of nutrients,

there being no other way to make them.

there can't not be carnivores.

dear god of hunter and of hunted,

i, too a body made of food, pray

to be eaten

rather than outconsume providence

and to love

the beauty of my fears.

And it brings forth our big and ultrasocial brains – that allow us not only amazing cleverness, but the capacity to share it, preserve it, and build on each other’s discoveries and strategies. All of this took massive heartless cruelty to bring forth.

Joseph’s way is to think in terms of a divine plan – but I offer to you that that is but a rhetorical flourish for orienting toward the beauty of life inseparable from its harsh pain.

Stephen Mitchell writes of the transformation that came over Joseph as he lay in that pit where his brothers had tossed him.

“The stone cistern where Joseph lay was the womb of his transformation. He had to descend to the depths of himself and stay there, in that inner darkness, without refuge, without hope. This was the only path that could lead him upward. Then he had to find his way through a world of paradox, where exile is homecoming, slavery is freedom, and not knowing is the ultimate wisdom. No one, of course, wants to suffer. And yet the fortunate among us manage to learn from our suffering what can be learned nowhere else. We become – clearly, joyously – aware of the cause of all suffering. The remembered pain drips into the heart, and an understanding dawns on us, even against our will, that there is a violent grace that shapes our ends. Humility follows as a natural result. We learn how to lose control. We discover that we never had it in the first place. . . . There is no humiliation or shame in any of this. It’s total surrender to what is. You discover that you have let go into an intelligence that is incomparably vaster than yours. . . . You stand in what’s left of you, and you die to self, and you keep on dying. It’s like a tree that lets go of its leaves. That beautiful clothing has fallen away, and the tree just stands there in the cold of winter, totally exposed, totally surrendered.” (Stephen Mitchell, Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness)

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

2020-11-16

Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness, part 1

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

I come today to re-tell an old story – to look again at what it tells us about being human and being animal. Before I get into Joseph and his brothers, let me say that I think a lot about stories – how we need them, and what happens when we don’t have them. Stories tell us who we are and make us who we are: individually and collectively.

Shared stories make a people a people. “I” and “me” are made of narrative – as are “we” and “us.” In these polarized times, where division rives the land, we don’t have shared story about who we are.

This contrasts sharply with the decade I was born in: the 1950s. The 1950s were, in many ways, an awful time. Jim Crow segregation and the racist attitudes that went with it were virulent. Gender oppression was stifling. LGBTQ folk largely stayed in the closet for their own safety. Anti-Semitism was worse.

It was also a time of cohesion. Very low income inequality, very low political polarization, tremendous levels of emotionally stable civic participation – churches, PTAs, civic clubs and bowling leagues had sky-high memberships.

In the mid-1950s, 89 percent of the US population was white. Moreover, the white numerical and cultural dominance was the settled norm: from the 1910 through the 1960 census, the percent of the population that was white never got below 88.6% or above 89.8%. Today the Census bureau says 60% of the population is nonhispanic white – which is a big change. It’s projected to fall below 50% before 2050.

We had a story. It was, frankly, a racist story. The history of humanity as I learned it in grade school was a mostly-Western history of Europeans accumulating great ideas and innovations, from the Egyptians, through Athens, Magna Carta, the Age of Faith, the Renaissance, the printing press, Western science, and democracy with a free press, independent judiciary, and a bill of rights. In the rap battle of cultures, Europeans, it seemed, need only say, “Plato, Shakespeare, Newton” – and drop the mic.

The story – in the version it came down to me – did not ever say "white people are genetically superior," or "white people are God's favorite." But the story also provided no other explanation for why these "great ideas and innovations" did not appear in the pre-Colombian Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, or East Asia. We now have some available stories that do address how the dominance of Europeans came about: stories that elucidate how European ability -- and willingness -- to cruelly subjugate the globe were products of particular conditions. Jared Diamond points to geography: the uniquely temperate climate, availability of multiple domesticable grains and multiple domesticable animals which allowed for accumulation of wealth and the rise of cities, which became hubs of innovation as well as centers of communicable disease (and, eventually, immunities). Other conditions include unintended effects of the sort of power dynamic that happened to develop between a centralized Christian church and decentralized secular rulers, which led to the Crusades, which provided the template for conquest and colonization all over the world.

Stories that identify the conditions that made one group of people interested in and capable of world domination are rather complicated, and they aren’t t broadly or well known. A lot of the general populace clings to the old story, tacitly accepting that there must be something special about white people. Among scholars who have looked most closely into the question, there’s disagreement about how much weight is carried by each of the various conditions, and the folks that approve school textbooks are even farther from consensus on a new story to tell.

We definitely needed to drop the racist, patriarchal story. The thing is: now we don’t have a shared story, which means we don’t know who we are as a people. Without knowing who we are as a people, the sense of belonging grows thing. We have more loneliness, more distrust, more isolation, alienation, depression, suicide. We need stories.

I don’t know if the people of the US will ever again have a unifying story that tells us who we are as a people. Yet we can tap into the vein of shared stories and keep them alive, even if they aren’t the sort that tell us who we are. So we come to the story of Joseph – which ironically is a chapter in the origin myth of the Jewish people. It has been, for millennia, precisely a story telling a people who they were. And it has come to be a part of the cultural storehouse for Christians as well as Jews, and for black, Hispanic, and white Americans – and some indigenous folk as well. Less so for Asian Americans, but many of them have been willing to learn the stories central to the mainstream culture of the nation they have moved to -- just as this mainstream culture has been willing to learn (some would say, appropriate) some Asian stories. (Perhaps you saw the latest Mulan movie?)

In other words: telling and re-telling stories from the Torah helps in the maintenance of a common narrative vocabulary. This won't do much to keep us from fighting each other. After all, the European powers warring which each other for a millennium and a half after the fall of Rome, and the two sides in America's Civil War, shared a common narrative vocabulary. But things are even worse when there isn't a shared narrative vocabulary.

In this case, it’s a story about what we might call the Way of Forgiveness. That’s what Stephen Mitchell calls it in his imaginative retelling and expansion of the Joseph story titled: Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness.

There are many kinds and levels of forgiveness. You can say it – “I forgive you.” You can say it and not mean it. You can say it and mean it, but still have not fully done it because a part of your heart continues to harbor a resentment.

Also, you can mean it, but never say it. Or neither say it, nor mean it, but nevertheless let go of your grievance – release all the resentment. Felicia Sanders, the mother of one of the nine victims killed by Dylann Roof in a Charleston church in 2015, told Roof, "I forgive you." I have no reason to doubt that she meant it. I just know that there are some times when forgiveness hasn’t actually happened just by being said – even when it’s meant.

The Way of Forgiveness though isn’t about the necessary and sufficient conditions for a single act or utterance to qualify as truly forgiving someone. The Way of Forgiveness is about a whole approach to life that isn’t about blaming – that isn’t about identifying specific wrongs and healing from them. Such identifying and healing might sometimes be necessary, but that's not what we see happen in the Joseph story.

Joseph never says, “I forgive you.” When his brothers come to beg his forgiveness -- which they don't do until after Jacob's death leaves them feeling vulnerable -- Joseph says to them:

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

I come today to re-tell an old story – to look again at what it tells us about being human and being animal. Before I get into Joseph and his brothers, let me say that I think a lot about stories – how we need them, and what happens when we don’t have them. Stories tell us who we are and make us who we are: individually and collectively.

Shared stories make a people a people. “I” and “me” are made of narrative – as are “we” and “us.” In these polarized times, where division rives the land, we don’t have shared story about who we are.

This contrasts sharply with the decade I was born in: the 1950s. The 1950s were, in many ways, an awful time. Jim Crow segregation and the racist attitudes that went with it were virulent. Gender oppression was stifling. LGBTQ folk largely stayed in the closet for their own safety. Anti-Semitism was worse.

It was also a time of cohesion. Very low income inequality, very low political polarization, tremendous levels of emotionally stable civic participation – churches, PTAs, civic clubs and bowling leagues had sky-high memberships.

In the mid-1950s, 89 percent of the US population was white. Moreover, the white numerical and cultural dominance was the settled norm: from the 1910 through the 1960 census, the percent of the population that was white never got below 88.6% or above 89.8%. Today the Census bureau says 60% of the population is nonhispanic white – which is a big change. It’s projected to fall below 50% before 2050.

We had a story. It was, frankly, a racist story. The history of humanity as I learned it in grade school was a mostly-Western history of Europeans accumulating great ideas and innovations, from the Egyptians, through Athens, Magna Carta, the Age of Faith, the Renaissance, the printing press, Western science, and democracy with a free press, independent judiciary, and a bill of rights. In the rap battle of cultures, Europeans, it seemed, need only say, “Plato, Shakespeare, Newton” – and drop the mic.

The story – in the version it came down to me – did not ever say "white people are genetically superior," or "white people are God's favorite." But the story also provided no other explanation for why these "great ideas and innovations" did not appear in the pre-Colombian Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, or East Asia. We now have some available stories that do address how the dominance of Europeans came about: stories that elucidate how European ability -- and willingness -- to cruelly subjugate the globe were products of particular conditions. Jared Diamond points to geography: the uniquely temperate climate, availability of multiple domesticable grains and multiple domesticable animals which allowed for accumulation of wealth and the rise of cities, which became hubs of innovation as well as centers of communicable disease (and, eventually, immunities). Other conditions include unintended effects of the sort of power dynamic that happened to develop between a centralized Christian church and decentralized secular rulers, which led to the Crusades, which provided the template for conquest and colonization all over the world.

Stories that identify the conditions that made one group of people interested in and capable of world domination are rather complicated, and they aren’t t broadly or well known. A lot of the general populace clings to the old story, tacitly accepting that there must be something special about white people. Among scholars who have looked most closely into the question, there’s disagreement about how much weight is carried by each of the various conditions, and the folks that approve school textbooks are even farther from consensus on a new story to tell.

We definitely needed to drop the racist, patriarchal story. The thing is: now we don’t have a shared story, which means we don’t know who we are as a people. Without knowing who we are as a people, the sense of belonging grows thing. We have more loneliness, more distrust, more isolation, alienation, depression, suicide. We need stories.

I don’t know if the people of the US will ever again have a unifying story that tells us who we are as a people. Yet we can tap into the vein of shared stories and keep them alive, even if they aren’t the sort that tell us who we are. So we come to the story of Joseph – which ironically is a chapter in the origin myth of the Jewish people. It has been, for millennia, precisely a story telling a people who they were. And it has come to be a part of the cultural storehouse for Christians as well as Jews, and for black, Hispanic, and white Americans – and some indigenous folk as well. Less so for Asian Americans, but many of them have been willing to learn the stories central to the mainstream culture of the nation they have moved to -- just as this mainstream culture has been willing to learn (some would say, appropriate) some Asian stories. (Perhaps you saw the latest Mulan movie?)

In other words: telling and re-telling stories from the Torah helps in the maintenance of a common narrative vocabulary. This won't do much to keep us from fighting each other. After all, the European powers warring which each other for a millennium and a half after the fall of Rome, and the two sides in America's Civil War, shared a common narrative vocabulary. But things are even worse when there isn't a shared narrative vocabulary.

In this case, it’s a story about what we might call the Way of Forgiveness. That’s what Stephen Mitchell calls it in his imaginative retelling and expansion of the Joseph story titled: Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness.

There are many kinds and levels of forgiveness. You can say it – “I forgive you.” You can say it and not mean it. You can say it and mean it, but still have not fully done it because a part of your heart continues to harbor a resentment.

Also, you can mean it, but never say it. Or neither say it, nor mean it, but nevertheless let go of your grievance – release all the resentment. Felicia Sanders, the mother of one of the nine victims killed by Dylann Roof in a Charleston church in 2015, told Roof, "I forgive you." I have no reason to doubt that she meant it. I just know that there are some times when forgiveness hasn’t actually happened just by being said – even when it’s meant.

The Way of Forgiveness though isn’t about the necessary and sufficient conditions for a single act or utterance to qualify as truly forgiving someone. The Way of Forgiveness is about a whole approach to life that isn’t about blaming – that isn’t about identifying specific wrongs and healing from them. Such identifying and healing might sometimes be necessary, but that's not what we see happen in the Joseph story.

Joseph never says, “I forgive you.” When his brothers come to beg his forgiveness -- which they don't do until after Jacob's death leaves them feeling vulnerable -- Joseph says to them:

"Do not be afraid! Am I in the place of God? Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today. So have no fear; I myself will provide for you and your little ones.” (Gen 50: 19-21)He reassures them he won't be seeking punishment or revenge, but doesn't say he forgives them. His own brothers were close to killing him. They sold him into slavery instead because, by a fluke, the opportunity to do so happened to arise. Joseph would seem to have a lot to forgive. But Joseph sees life as working out for the best – as under a divine plan. All things happen as they should, so there’s never a grudge, and never a need for a specific process of releasing the grudge. How does that work? And how does Joseph's story tell us something that will help us make sense of our world? I’ll look into that in part 2.

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Intro

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2 "

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

STORY (adapted from Genesis, illustrations by R. Crumb)

Jacob had 12 sons -- Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph, and Benjamin – and one daughter, Dinah. The eleventh son, Joseph, was Jacob’s favorite.

When Joseph was seventeen, one day, after shepherding the flock with his brothers he brought a bad report of his brothers to their father. So his brothers didn’t like Joseph.

Jacob made for Joseph a long robe with sleeves. But when his brothers saw that their father loved Joseph more than all his brothers, they felt bad and further disliked Joseph.

Once Joseph had a dream, and when he told it to his brothers, they hated him even more. He said to them, “Listen to this dream that I dreamed. There we were, binding sheaves in the field. Suddenly my sheaf rose and stood upright; then your sheaves gathered around it, and bowed down to my sheaf.” His brothers said to him, “Are you indeed to reign over us?”

One day when many of the brothers were tending flocks far from home, Jacob sent Joseph to see how things were going. From a distance, the brothers saw Joseph coming, and they made a plan to get Joseph out of their lives.

So when Joseph came to his brothers, they stripped him of his robe, the long robe with sleeves that he wore; and they took him and threw him into a pit.

Then they saw a caravan of Ishmaelites coming by. This gave them the idea to sell Joseph to the Ishmaelites to be their slave. And that’s what they did.

The Ishmaelites took Joseph to Egypt, where they re-sold him to Potiphar, Pharaoh’s captain of the guard.

Joseph was a good thinker and planner, and helped Potiphar prosper. Potiphar trusted Joseph to manage almost all his affairs.

Then one day, Potiphar’s wife wanted Joseph to do something that Joseph knew Potiphar wouldn’t want him to do. Joseph refused. Potiphar’s wife told Potiphar a lie about Joseph, which cause Potiphar to have Joseph thrown in prison.

Joseph was so inherently helpful and talented, that soon he had earned the complete trust of the chief jailor, who put Joseph in charge of managing the prison.

Joseph could interpret dreams. He gave such insightful interpretations of the dreams of some of the other prisoners that word even got back to Pharaoh about it.

So when Pharaoh had two disturbing dreams one night, he sent for the prisoner Joseph to interpret them. This was Paraoh’s dream: seven fat cows were swallowed up by seven thin cows. In the second dream, seven ears of grain, plump and good, were swallowed up by seven ears thin and blighted.

Joseph told Pharaoh that the seven fat cows and the seven plump ears of grain represented seven years of plenty, which would be followed -- swallowed up -- by seven years of famine. What Pharaoh needs to do, said Joseph, is appoint supervisors to make sure food is stored up during the good years to see Egypt through the lean years.

Pharaoh released Joseph from prison and appointed him the overseer of the preparations for the famine years. Suddenly, Joseph was very powerful, and heaped with the riches corresponding to his station.

When the famine came, it affected all the surrounding areas, including Canaan, where Joseph’s father, brothers, and sister were. When Jacob heard that Egypt had storehouses of grain, he sent his sons to Egypt to buy some.

When the brothers came before Joseph seeking food, they didn’t recognize Joseph – though Joseph recognized them. When Joseph threatened to have Benjamin thrown into enslavement, Judah begged, “let him go – take me instead.”

Then Joseph, weeping, revealed himself to his brothers. He had them and their father, Jacob, moved to Egypt, where he ensured their survival through the famine.

The brothers finally came to Joseph to beg forgiveness for their crime. They offered themselves as his slaves. Joseph and all the brothers were crying.

Joseph said, “Do not be afraid! Even though you intended to do harm to me, it has put me in position to preserve a numerous people. I will provide for you and your little ones.”

See: "Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 1"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2 "

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 2 "

"Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness: Part 3"

STORY (adapted from Genesis, illustrations by R. Crumb)

Jacob had 12 sons -- Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph, and Benjamin – and one daughter, Dinah. The eleventh son, Joseph, was Jacob’s favorite.

When Joseph was seventeen, one day, after shepherding the flock with his brothers he brought a bad report of his brothers to their father. So his brothers didn’t like Joseph.

Jacob made for Joseph a long robe with sleeves. But when his brothers saw that their father loved Joseph more than all his brothers, they felt bad and further disliked Joseph.

Once Joseph had a dream, and when he told it to his brothers, they hated him even more. He said to them, “Listen to this dream that I dreamed. There we were, binding sheaves in the field. Suddenly my sheaf rose and stood upright; then your sheaves gathered around it, and bowed down to my sheaf.” His brothers said to him, “Are you indeed to reign over us?”

One day when many of the brothers were tending flocks far from home, Jacob sent Joseph to see how things were going. From a distance, the brothers saw Joseph coming, and they made a plan to get Joseph out of their lives.

So when Joseph came to his brothers, they stripped him of his robe, the long robe with sleeves that he wore; and they took him and threw him into a pit.

Then they saw a caravan of Ishmaelites coming by. This gave them the idea to sell Joseph to the Ishmaelites to be their slave. And that’s what they did.

The Ishmaelites took Joseph to Egypt, where they re-sold him to Potiphar, Pharaoh’s captain of the guard.

Joseph was a good thinker and planner, and helped Potiphar prosper. Potiphar trusted Joseph to manage almost all his affairs.

Then one day, Potiphar’s wife wanted Joseph to do something that Joseph knew Potiphar wouldn’t want him to do. Joseph refused. Potiphar’s wife told Potiphar a lie about Joseph, which cause Potiphar to have Joseph thrown in prison.

Joseph was so inherently helpful and talented, that soon he had earned the complete trust of the chief jailor, who put Joseph in charge of managing the prison.

Joseph could interpret dreams. He gave such insightful interpretations of the dreams of some of the other prisoners that word even got back to Pharaoh about it.

So when Pharaoh had two disturbing dreams one night, he sent for the prisoner Joseph to interpret them. This was Paraoh’s dream: seven fat cows were swallowed up by seven thin cows. In the second dream, seven ears of grain, plump and good, were swallowed up by seven ears thin and blighted.

Joseph told Pharaoh that the seven fat cows and the seven plump ears of grain represented seven years of plenty, which would be followed -- swallowed up -- by seven years of famine. What Pharaoh needs to do, said Joseph, is appoint supervisors to make sure food is stored up during the good years to see Egypt through the lean years.

Pharaoh released Joseph from prison and appointed him the overseer of the preparations for the famine years. Suddenly, Joseph was very powerful, and heaped with the riches corresponding to his station.

When the famine came, it affected all the surrounding areas, including Canaan, where Joseph’s father, brothers, and sister were. When Jacob heard that Egypt had storehouses of grain, he sent his sons to Egypt to buy some.

When the brothers came before Joseph seeking food, they didn’t recognize Joseph – though Joseph recognized them. When Joseph threatened to have Benjamin thrown into enslavement, Judah begged, “let him go – take me instead.”

Then Joseph, weeping, revealed himself to his brothers. He had them and their father, Jacob, moved to Egypt, where he ensured their survival through the famine.

The brothers finally came to Joseph to beg forgiveness for their crime. They offered themselves as his slaves. Joseph and all the brothers were crying.