Preface: The Mechanically Moral Universe

The mechanically moral universe thesis says the universe rewards virtue and punishes wickedness. If virtue goes in, you get reward out; wickedness in, punishment out – as if the universe were a great moral machine, a cosmic meritocracy. Wisdom from the Hebrew Bible has for thousands of years reminded readers that life is not all about getting what one deserves.

First, from the book of Ecclesiastes, chapter 9, verse 11:

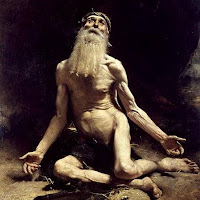

“Again I saw that under the sun the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to the skillful; but time and chance happen to them all.” (NRSV)Second, the Book of Job. Here is Michael Sandel’s exposition.

“A just and righteous man, Job is subjected to unspeakable pain and suffering, including the death of his sons and daughters in a storm. Ever faithful to God, Job cannot fathom why such suffering has been visited upon him.... As Job mourns the loss of his family, his friends (if one can call them friends) insist that he must have committed some egregious sin, and they press Job to imagine what that sin might be. This is an early example of the tyranny of merit. Armed with the assumption that suffering signifies sin, Job’s friends cruelly compound his pain by claiming that, in virtue of some transgression or other, Job must be to blame for the death of his sons and daughters. Although he knows he is innocent, Job shares his companions’ theology of merit, and so cries out to God asking why he, a righteous man, is being made to suffer. When God finally speaks to Job, he rejects the cruel logic of blaming the victim. He does so by renouncing the meritocratic assumption that Job and his companions share. Not everything that happens is a reward or a punishment for human behavior, God proclaims from the whirlwind. Not all rain is for the sake of watering the crops of the righteous, nor is every drought for the sake of punishing the wicked....God confirms Job’s righteousness but chastises him for presuming to grasp the moral logic of God’s rule. This represents a radical departure from the theology of merit....In renouncing the idea that he presides over a cosmic meritocracy, God asserts his unbounded power and teaches Job a lesson in humility. Faith in God means accepting the grandeur and the mystery of creation, not expecting God to dispense rewards and punishments based on what each person merits or deserves.” (The Tyranny of Merit 36)

Grace and Solidarity

Grace and solidarity: these two seem to me to pretty well sum up what makes a good life. Grace: the freely given, unmerited gifts you did not earn and do not deserve. Like being alive. Like being more or less healthy – healthy enough and pain-free enough to be able to be reading this right now. Like air, and the feel of breath in your lungs. Like sunlight, rain, autumn leaves, or a warm breeze on this first day of Spring. You didn’t earn those things. You’ve done nothing to deserve them. They are free gifts – grace.

You might choose to not notice them. But a life of richness and depth is one that is constantly seeing grace everywhere – the beauty all around us.

And: solidarity. We’re not in it just for ourselves. We’re in this together. We are here for each other – what else?

Grace and solidarity. As those are the crux of a good life, it behooves us to attend to whatever undermines the place in our lives of grace and solidarity.

The Corrosive Meritocratic Ethic

An emphasis on merit – on who deserves what – is the killer of both grace and solidarity. The meritocratic ethic says that life is all about two other things: ability and hard work, also known as talent and effort, or capability and motivation. From these two come your merit, your deservingness for success and status. The meritocratic ethic casts life as a zero-sum game – a competition, and, as per the nature of competition, winning means causing someone else’s loss. Michael Sandel, in The Tyranny of Merit, says of the meritocratic ethic:

“Among the winners, it generates hubris; among the losers, humiliation and resentment. These moral sentiments are at the heart of the populist uprising against elites. More than a protest against immigrants and outsourcing, the populist complaint is about the tyranny of merit. And the complaint is justified. The relentless emphasis on creating a fair meritocracy, in which social positions reflect effort and talent, has a corrosive effect on the way we interpret our success (or the lack of it).” (25)The meritocratic ethic produces a

“smug conviction of those who land on top that they deserve their fate, and that those on the bottom deserve theirs, too.” (25)For those on the bottom, the meritocratic ethic means either frustration or humiliation and despair. Either they believe that the system fails to recognize their merit and denies them opportunities to use it – or, perhaps worse, they accept that meritocratic sorting has been more-or-less fair, and they just aren’t good enough to have earned any better than they got.

The Rise of Meritocracy

The grip of the meritocratic ethic has been growing through the post-World War II era. A 1958 book, The Rise of the Meritocracy, by British sociologist Michael Young, described meritocracy as a dystopia.

By 1958, the British class system had been breaking down for some time. The old aristocracy had been giving way to a system of educational and professional advancement based on merit. In many ways, this was a good thing. Gifted children of the working class could develop their talents and escape from a life of manual labor. But the old system at least had the weird advantage that everybody knew it was unfair. Neither the Lords nor the working class believed they deserved their status – which tempered the arrogance of the upper-class and precluded despair for the laborers. The working class knew their situation wasn’t their own fault.

Michael Young, writing from an imagined position in the year 2033 (75 years in his future), said:

“Now that people are classified by ability, the gap between the classes has inevitably become wider. The upper classes are no longer weakened by self-doubt and self-criticism. Today the eminent know that success is just reward for their own capacity, for their own efforts, and for their own undeniable achievement. They deserve to belong to a superior class. They know, too, that not only are they of higher caliber to start with, but that a first-class education has been built upon their native gifts.” (The Rise of the Meritocracy 106)Meanwhile the losers in the meritocracy are resentful at the arrogance of the winners while also humiliated with the knowledge that they have no one to blame but themselves.

“Today, all persons, however humble, know they have had every chance.... Are they not bound to recognize that they have an inferior status – not as in the past because they were denied opportunity; but because they ARE inferior? For the first time in human history, the inferior man has no ready buttress for his self-regard.” (108-9)Michael Young’s tale from 1958 predicted that in 2034 the less-educated classes would rise up in a populist revolt against the meritocratic elites. We can now say that the revolt that Young predicted came 18 years ahead of schedule, in 2016, when Britain voted for Brexit and America voted for Trump.

Centering the Field of Competition

While Democratic candidates, and many Republicans were repeatedly intoning that everybody ought to be able to go as far as their talent and hard work could take them, Trump never said that. His fans knew that the meritocratic game cast them as the losers, that their work no longer had much dignity, or even afforded much of a living any longer. Their feelings of both humiliation and resentment proved potent.

If the game being played on the field is one that inherently has winners and losers, then leveling the playing field does nothing to revitalize civic life, does nothing to foster a sense that we’re all in this together, does nothing to shore up solidarity. Is that the world we want? Hubris, arrogance, for the winners and despair and humiliation for the losers?

There will always be a place for competition – for working hard to win, for reaping rewards when you do, and for coping with the disappointment when you come up short. But even competition can be approached in a cooperative spirit – as an exercise in working together to spur each other to greater excellence. This way, I’m not trying to win for winning’s sake. I’m trying to hold the bar as high as I can to help you practice rising to it, while understanding that you’re doing the same for me. The point isn’t the winning or losing – the point is working together to develop our excellence. The win or loss is just feedback we get along the path of that pursuit.

Sandel writes that,

“a perfect meritocracy banishes all sense of gift or grace. It diminishes our capacity to see ourselves as sharing a common fate. It leaves little room for the solidarity that can arise when we reflect on the contingency of our talents and fortunes. This is what makes merit a kind of tyranny, or unjust rule.” (The Tyranny of Merit 25)There’s a lot of talk of leveling the playing field – and for those aspects of life where there should be competition, the playing field does need to be level. Where we decide to have competitions for some prize or other – a college admission, a job, an elective office – it is right and proper that we ensure that the competition be fair.

But when we make the levelness of playing field the major concern, we forget that public life isn’t all about the competition. It’s about recognizing that we’re in this together. It’s about standing as equals with each other as neighbors, engaged in the work of citizenship (whether we are legal citizens or not).

It’s not all about standing as competitors in a zero-sum game. We may, from time to time, want or need to meet on a competitive playing field, but meritocracy puts that competition at the center of public life, instead of putting our shared civic enterprises at the center.

Meritocracy also puts that competition at the center of our individual sense of who we are. Meritocracy defines us – to each other and to ourselves -- by what we deserve, what we earn. It teaches us relative disregard for all the range of life that isn’t, or shouldn’t be, marketable.

The Perfect Meritocracy: Sports

"Level playing field" is a sports metaphor, and sports is often held up as the perfect meritocracy. There’s ability, and there’s the hard work of training to maximize that ability – and that’s it. In sports, it’s apparently easy to believe that everybody really can go as far as their ability and hard work will take them.

But even in this most perfect of meritocracies, let’s notice that the race isn’t always to the swift nor the battle to the strong. The ball can take a funny bounce. Sometimes a bad hop can determine the outcome of a championship game. It’s luck.

Suppose there is no funny bounce or gust of wind. Suppose, say, a basketball game comes down to one free throw, and an 80% shooter is on the line. Her talent and her training got her to the point where she’s an 80% shooter. But whether this one shot will be one of the 80% she makes or one of the 20% she misses – that’s luck.

There’s always luck. And let’s dig deeper. Where did the ability and the training come from?

Next: digging deeper

No comments:

Post a Comment